A Decade with Erikson

A love letter reflecting on 10 years with The Malazan Book of the Fallen.

~

The summer of 2012, having recently finished off the last (available) book of A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin, I was looking for something new. Something similar - something epic and dramatic and imaginative. Two possibilities came up, neither of which had I heard of before: The Black Company and The Malazan Book of the Fallen.

We went to a bookstore (remember those?) and I found the first book of both series. I didn’t know which one to choose. But then I saw on the jacket of Gardens of the Moon, the first Malazan book, a testimonial from Glen Cook, author of The Black Company, the other series I was considering. It read:

I stand slack-jawed in awe of The Malazan Book of the Fallen. This masterwork of imagination may be the high water mark of epic fantasy. This marathon of ambition has a depth and breadth and sense of vast reaches of inimical time unlike anything else available today. The Black Company, Zelazny’s Amber, Vance’s Dying Earth, and other mighty drumbeats are but foreshadowings of this dark dragon’s hoard.

I figured if Glen Cook thought that his books weren’t as good as the Malazan ones, well… he’d know as well as anyone.1 At that point, I had no idea where these books would take me, and how much they would come to mean.

Two weeks ago - nearly ten years later - I finished my second read-through2 of Malazan’s main ten-book series. The series (including the 20+ additional books in the Malazan universe, all of which I have read) has been with me through moves, through relationships, through challenges - through it all. The books aren’t perfect,3 but I struggle to think of anything that has been as consistent - and consistently impactful over the last decade of my life.4

To honor my time (so far) with these ten monstrous books, here are ten reflections on the series, its themes, its marvelous characters, and its authors.

art by RoeeateR

Exquisite structure and care

One small thing that I greatly appreciate about Erikson is his consistency. One key difference between The Malazan Book of the Fallen and A Song of Ice and Fire is that Erikson is far more consistent. Frankly, he’s prolific. Erikson put out the main series comprising ten books (and 3.3 million words) in only 12 years.

And Erikson didn’t rush. The books are exquisitely constructed, with not a word out of place. Erikson credits his background in short stories:

A couple years back it occurred to me that I never really learned how to write a novel: I learned how to write short stories, and when I set to writing a novel I simply scaled up. So you can consider the ten book series as the longest short story ever written. […] I approached every line as if under the burden of carrying as much information as it could withstand, balanced against the elegance, rhythm, word-choice, of the sentence itself. Just like in a short story.

In all but the last book, the book’s part and chapter structure is exactly the same as well, even with wildly varying settings and storylines: 4 parts, 6 chapters each. Thus, the pacing is consistent - and it works. By the time Erikson really challenges you - spending the first quarter of the fourth book providing the origin story for an important character you have not even heard of before - you know you are in good hands.5

Do I intentionally set out to frustrate the reader? What an outrageous notion. Of course I do.

art from a limited edition book cover

A collaborative project

Another thing that makes Malazan special is that it is a collaboration between two friends. They started out building the world together as part of a GURPS role-playing game (think a custom version of Dungeons & Dragons).

As the game became a screenplay, and then a series, then a full-on fantasy universe, the collaboration didn’t stop. While Erikson wrote the main 10-book series, and is honestly the better writer, his friend and collaborator Esslemont has written plenty of great books. They read faster and easier, making for a nice counterpoint to the serious eloquence of Erikson.

In a world obsessed with the idea of the lone genius, this series is a reminder - like Inuit printmaking, theatre and film, and sport (among other things) - of the amazing things humans can do when working together.

Art imitating life

The American composer John Cage once said that there is no separation between art and life. He explored that notion through a variety of techniques, many of them aleatory - that is, having to do with chance. Recognizing the confounding chaos of the real world, he sought to imitate it through randomness.

Coming from the world of A Song of Ice and Fire, major characters dying at surprising moments was no surprise. But there is a subtle difference between the mortality of George R.R. Martin’s world and that of the Malazan one. While the drama of the former is contrived and melodramatic, the timing and circumstances of death in the latter, though shocking, are often more natural in their randomness: a true randomness that is only possible through the roll of a 20-sided die.

The aleatory aspects of Erikson and Esslemont’s world-building make truly epic, convergent moments all the more dramatic. When I learned that one of the most intense moments of the entire series, in Toll the Hounds, was rolled a “natural 20,” I couldn’t hold in the emotion. I broke into tears - the perfection of it all, and the unbelievable sacrifice of that moment, was simply too much to handle.

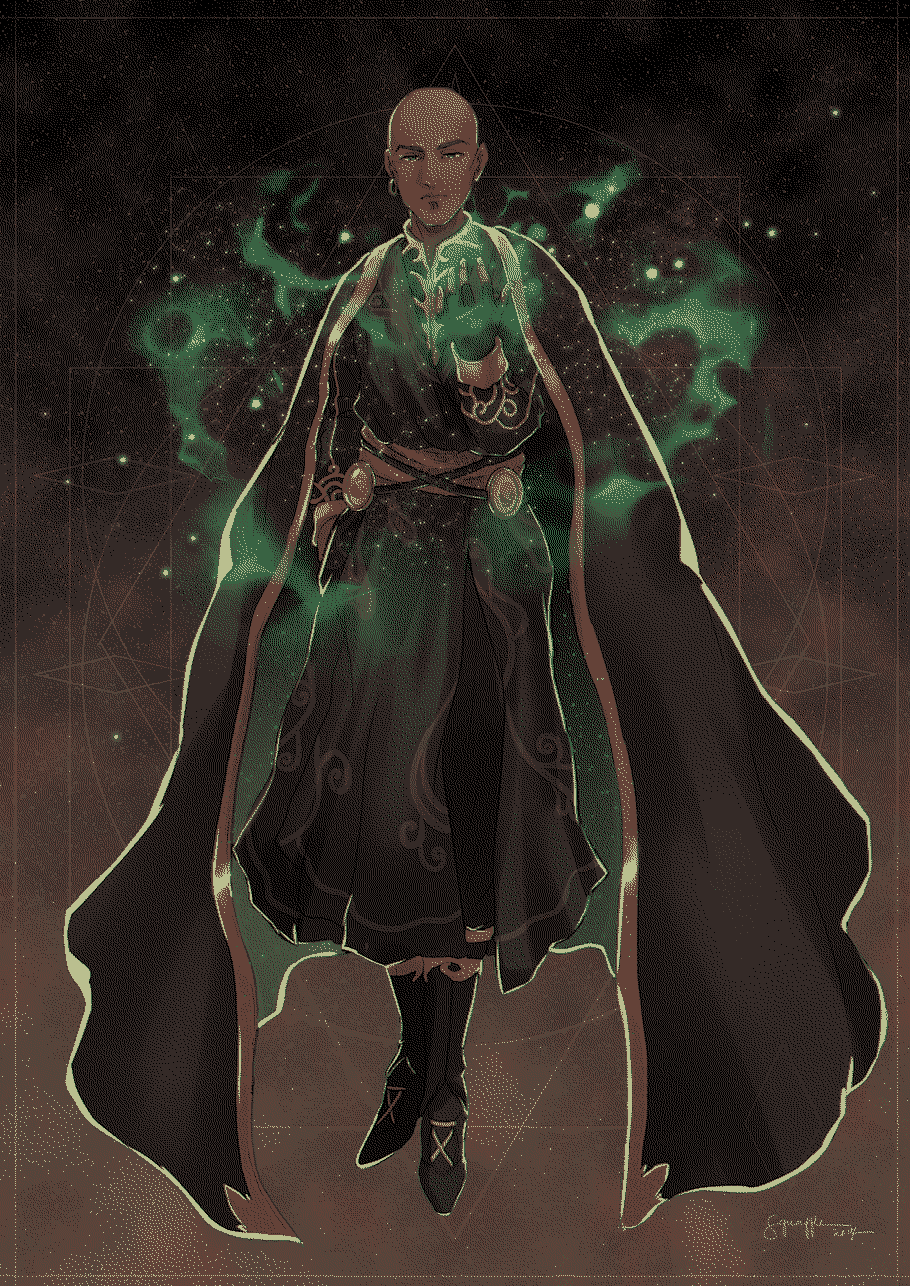

art by Squaffle

Histories

In the Malazan world, history is layered under characters’ feet, like sediment. And yet, it is also alive, walking beside them.

Many of Erikson’s chapters open with descriptions of the landscape - often ochre-colored - and the unseen layers underneath. He reveals the undercurrent (no pun intended), or perhaps the histories of a distant landscape, from agriculture and logging causing erosion to dried up seabeds, the dust of clay pots, and the bones of plains mammals long extinct. It isn’t surprising, then, to learn that he (and Esslemont?) was trained as an archeologist/anthropologist.

He is preoccupied, in particular, with the question of preservation?

The world, [he] knew, was indifferent to the necessity of preservation. Of histories, of stories layered with meaning and import. It cared nothing for what was forgotten, for memory and knowledge had never been able to halt the endless repetition of wilful stupidity that so bound peoples and civilizations.

In the main novels, the remnants of the past come back, sometimes at pivotal moments. Both a monkey-like precurser to humans and a nanderthal-like race appear from the ashes to make an impact on the world during a time of dramatic change. They are sometimes like (fallible Greek/Roman) gods,6 sometimes like zombies, and other times, just like us.

Some ancient races and characters are also representative of deeper ideas. As I wrote in the land acknowledgment for this website:

In my favorite book series, The Malazan Book of the Fallen, history is alive. It is personified by gods, ascendants, and other immortal beings, each with their own story. In some ways, they are more like impulses than characters - or ideas that just won’t die. They walk the earth, drifting from conflict to conflict, living myths long detached from the circumstances that forged them, seeking always an elusive sense of fulfillment that never comes.

Good lives on and adapts, but so too does evil. Like those ghoulish immortals of the Malazan world, some of our darkest ideas, as a species, never seem to go away. Supremacy. Scarcity. Materialism. Individualism. Some folks say that those who do not know the past are doomed to repeat it - and perhaps they are right. Today, however, it is as clear as ever that the past is not done with us, and knowing it is not enough. The evils of the past are not gone, and will not be going away anytime soon.

art by Shadaan

The waters are rising

It is not enought to wish for a better world for the children. It is not enough to shield them with ease and comfort. If we do not sacrifice our own ease, our own comfort, to make the future’s world a better one, then we curse our own children. We leave them a misery they do not deserve; we leave them a host of lessons unlearned.

Erikson’s fiction subtely - and sometimes not so subtely - comments upon a variety of contemporary issues7.

Every work of art is contextual, bound to its time of creation, and no matter how inventive a fantasy world, it can’t help but derive its inspiration from the real one. It doesn’t help that, these days more than ever, much of the (and here I’ll invent a word on the fly) ethosphere (as in, the ethos of the culture surrounding you, an alternative for Zeitgeist) is itself a fantasy, created by the incessant needs of market forces, consumerism, titillation and spectacle.

One area where this is particularly clear is his approach to climate change. In the Malazan world, the ice fields are menting, the oceans are rising, and there are alternating droughts, plagues, and floods, forcing migration and death. (Sound familiar?) The earth, embodied by a god, is itself ill, and in need of saving from the harmful extraction of humanity and the ancient races that have adopted our practices.

Themes of nature being in conflict with humanity are found throughout the stories. As a fictional poet says:

The shore does not dream of you.

Throughout the majority of the series, however, Erikson endeavors to dig deeper and connect the sociaetal problems we face today with the fundamental ones we find within ourselves.

We have a talent for disguising greed under the cloak of freedom. As for past acts of depravity, we prefer to ignore those. Progress, after all, means to look ever forward, and whatever we have trampled in our wake is best forgotten.

Humanity’s obsession with progress is a frequent target:

The notion of progress is an illusion.

For better or for worse, the Malazan books are not where to go for solutions to humanity’s problems. But Erikson’s strength is in creating deep, amazing characters that are easy to connect with, and through them, showing us, over and over again, all of our problems, yes - but also the amazing compassion that we can find within.

art by Dejan Delic

The common soldier

Thank not for a fair bargain; honour it.

In the series, the great majority of characters are the soldiers (or former soldiers) of an empire spreading across the world, bringing peace, capitalism, and all of the messy business that comes with it.

By the time we join the story, a lot of the conquering is done, and they are beginning to face a series of challenges to the world that make even the gods tremble, and for which the great skill of these warriors is required, naturally, to save humanity and/or the earth.

That sounds very epic and all, but it isn’t really what the books are about.

In many ways, these soliders are like all of us. Like most of us, the common soldier does not choose their circumstances. They need the coin, or their family does. All they can do is keep marching forward, step after step, taking on challenges as they arrive. Along the way, growing close with the people beside them, whether chosen or not.

As a fan of almost any long series would agree, over time, the characters can become your friends. You build a sort of parasocial - one-way - relationship with them. Re-reading the series was like checking in, just to see how their doing and reminisce about old times. There are all these little inside jokes that only a Malazan reader can pick up.8 And when you relive the sacrifice or loss of beloved characters, you cry anew,9 with the full knowledge of what their future holds.

Many of the characters are also old friends with one another. By the time you join up with the Bridgeburners in the first book, they’ve been on the road for years. They have long histories with one another, and like everything in these books, Erikson is not about to just tell it to you. You have to put it together, piece by piece, and when you see the full picture, it is really satisfying.

“Save your explanations, I got some questions for you first and you’d better answer them!”

“With what? Explanations?”

“No. Answers. There’s a difference -

“Really? How? What difference?”

“Explanations are what people use when they need to lie. Y’can always tell those, ‘cause those don’t explain nothing and then they look at you like they just cleared things up when really they did the opposite and they know it and you know it and they know you know and you know they know that you know and they know you and you know them and maybe you go out for a pitcher later but who picks up the tab? That’s what I want to know.”

“Right, and answers?”

“Answers is what I get when I ask questions. Answers is when you got no choice. I ask, you tell. I ask again, you tell some more. Then I break your fingers, ‘cause I don’t like what you’re telling me, because those answers don’t explain nothing!”

Although some relationships are already in place when you enter the Malazan world, there are plenty more that you get to see begin. All of these relationships between characters, evolving over years and years, are something to behold. Throughout the books, whether with that first troop, or amongst other characters, Erikson is exceptional at developing vivid, vivacious relationships between characters.

The books are full to the brim with gritty comraderie. Witty banter. Romance, often short-lived. Friendships hardened in battle, or in hunger, or simply tempered under the relentless march of time. The characters are so vivid, so relateable - you can’t help but be drawn in. Whether it is troops of soldiers, theives, mercenaries, mages, or dragons, these books are full of conversations where the reader feels lucky to be a fly on the wall.

Though common, and often hilarious, they are anything but simple. Many of them also speak with eloquence, and with percipience - in their own way.

‘Aye.’ It’s a good word, I think. More a whole attitude than a word, really. With lots of meaning in it, too. A bit of ‘yes’ and a bit of ‘well, fuck’ and maybe some ‘we’re all in this mess together’. So, a word to sum up the Malazans.

Tragedy is an unavoidable part of all of our lives. For many, like it has for me, tragedy has come in the form of unexpected death.

From these soldiers, I have learned about the inevitability of it all. About failure. About mortality. And how to continue on, even when it seems like it isn’t worth it any longer.

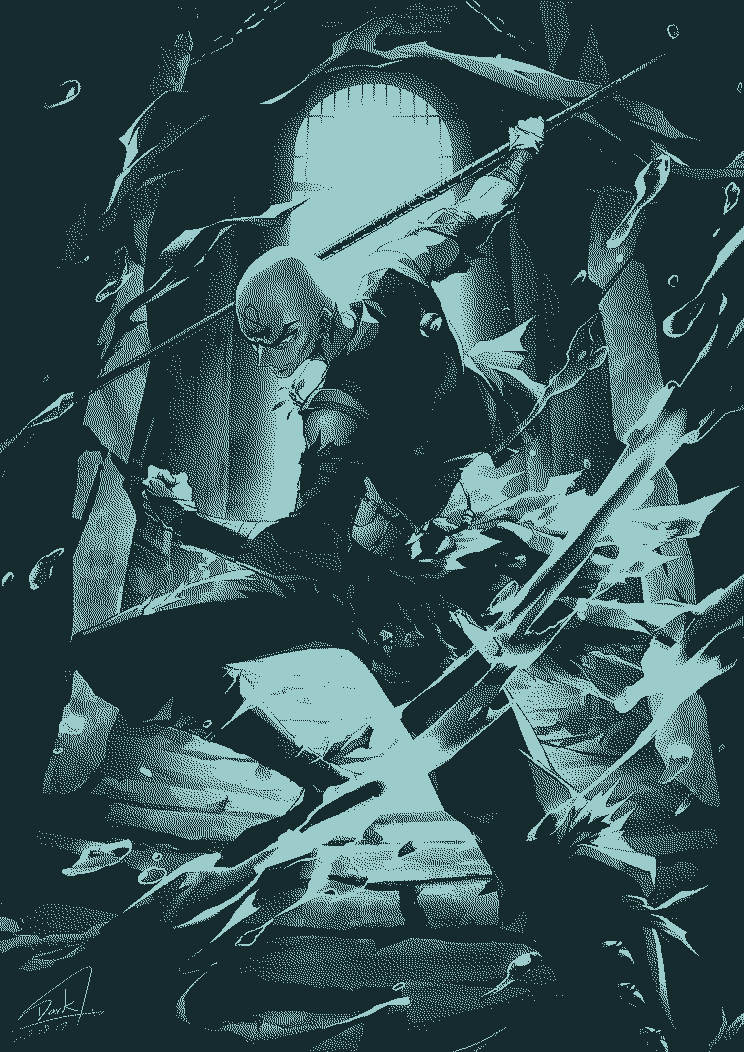

art by DarkHHHHHH

Subverting the archetypes

Erikson and Esslemont’s subversion of fantasy stereotypes is everywhere,10 and yet, they barely bring attention to it. Here are a few examples that come to mind:

- Ogres are wizards, basically - living in tall towers, alone, and smarter and more powerful than most other races

- Dinosaurs developed an apartheid technocratic society that was torn apart by a race war

- The dark elves are noble, while the light elves are evil, and gray elves are tribal

None of these reversals are flippant, casual, or have the veneer of being contrarian just for the sake of it. Compared to other subversive series I’ve encountered, I really appreciate how these world-building choices do not become the focus of the story. Characters are complex, and regularly defy expectation, not because of what they are or where they come from, but because of who they are.

For example, one of the most prominent characters of the series - introduced during the first quarter of the fourth book - is a giant that is constantly exploring (at times subverting, at times deconstructing) the barbarian fantasy / noble savage archetype. This, along with the other ideas Erikson plays with, have a purpose beyond giving Tolkien the bird. They serve the story, thematically, and at times make the reader look in the mirror, and think about their own contradictions.

art by Tsabo6

A world in gray

In another departure from traditional fantasy stories, in the Malazan world, nothing is purely black or white. There is no perfect hero, no perfect villain. Characters’ lives do not have some divine purpose, beyond the purposes they find for themselves.

In Malazan, the reader is treated to an amazingly varied exploration of why people behave the way they do. And I love it. The dark humor, the bright heroism, the drama of light and dark, life and death, not-quite-good and and not-quite-evil - I love it all.

As a kid, I loved classic stories of good and evil. From Harry Potter to The Ranger’s Apprentice and The Lord of the Rings, I dove right into the perspective of the heroes, off to vanquish their “dark lord.” In many ways, the Book of the Fallen is tailor-made for the man that that little boy is becoming. As I’ve grown, I’ve come to realize that none of us are simply “good” or “bad.” But I still believe in heroes - and that all of us have the potential to change the world.

art by Michael Komarck

The true fantasy of the Malazan world

Fantasy literature is an escape. It is indulgent. 11 It can be epic. It has magic, and heroes, and monsters. At the heart of traditional escapist literature, however, is a fundamental separation from our world: a world of clear good and evil. Without it, what is left?

The Book of the Fallen’s fantasy is simple: that anyone, no matter weak, no matter how small, can change the world.

If you know me, you know how tantalizing that is. Changing the world - fixing things - is my secret goal. Not that I think I can! Provided I ever even have a chance, I know I’m likely to fail. And that’s what so amazing about escaping from this effing planet into another alternative history, an alternate world, where for everyone, power lies within.

art by BlazeMalefica

Inspiration

I hadn’t written anything on this blog since May of last year. I have a list of excuses: a breakup, this unending pandemic, moving three times, and going on a five-month trek across the US. But the real reason was that I’ve been feeling like I have nothing to say. The guilt crept in, too, and froze me in place. I lost my flow.

He offers some words of wisdom to those, like me, who struggle with their own writing practice:

Writing and the need to keep doing it may seem like a curse at times, but it’s the opposite. It’s your weapon, and your armor. It’s the white hot core inside you that no heel can ever crush.

Writing, like all art, is (for me) an ongoing reconciliation with failure. And writing is keeping the negotiation alive: there’s no crawling out of, only crawling through, and guess what? It’s fine. It’s livable, when nothing else - for you and for me - is. So take a breath, make a fist, and set out to beat your demons to a pulp.

Well, that’s what I’ve tried to do, here. I’m pushing through, getting some proverbial ink on the page. And what better topic to start with than the work of Erikson himself?

As I try to continue to write, I’ll try to remember why it is important. In Erikson’s words:

We all need to argue against reality, to rail against it, in fact. For all the shit out there, all the fucked up idiocy of a culture and civilization bent on self-destruction, your only answer - your only riposte - is to face that blank screen or blank page, and to conjure up yet one more gesture of humanity. Really, what else can you do?

-

Cook was actually a big influence on Erikson and the Malazan books, and Erikson also has quotes on Black Company anthologies, fwiw. But I didn’t know that at the time. ↩︎

-

Re-reading this series is a must, assuming you liked it the first time. Here’s Erikson’s take: “Did I intentionally design the series for re-reads? A couple years back it occurred to me that I never really learned how to write a novel: I learned how to write short stories, and when I set to writing a novel I simply scaled up. So you can consider the ten book series as the longest short story ever written. I approached every line as if under the burden of carrying as much information as it could withstand, balanced against the elegance, rhythm, word-choice, of the sentence itself. Just like in a short story. It’s no wonder the books do well as re-reads, because let’s face it, who reads a novel as if it was short story? The text is packed. It’s bursting at the seams. I must have been insane.” ↩︎

-

Some people go so far as to say that this is the peak of fiction, period. I wouldn’t go quite that far, as much as I love it. On occasion, Erikson can be a bit long-winded and will get on a bit of a soapbox. The melodrama can also overflow on occasion. And when a minor character starts thinking about ther childhood and giving you their whole backstory, well, their fate is a bit obvious. They might as well put on a red shirt and explore an alien planet with Captain Kirk. But I am obviously in love with these books, despite their little faults. ↩︎

-

A few friends come to mind, and of course my family, but that’s about it. ↩︎

-

The farther you get into the series, and the more characters you know, the more time the books spend characterizing all of them. I think this is part of why the secind and third books are often the highest rated - once you start the fourth one, it isn’t about the individual book anymore. You’re in it for the long haul. ↩︎

-

The gods in this are fallible, much like the Greek or Roman ones of old. Actually, it strikes me that the epic poems of that period were likely a tremendous influence on Erikson. Every chapter of the series begins with a poem or historical excerpt, and many of them come from a bard and composer of epics reminiscent of The Iliad or The Odyssey. ↩︎

-

While Erikson is an outspoken supporter of the Movement for Black Lives, and he explores concepts of indigeneity (although often from a colonial perspective), the discussion in the “Malazan Empire” Facebook group (before I left that platform) was a reminder that his intended themes do not come across for everyone. ↩︎

-

“You wouldn’t get it. You had to be there. Well, you have to have read thousands of pages, I mean.” ↩︎

-

The series brings me to tears on a regular basis. ↩︎

-

On the series’ TVTropes.org page, there are obviously plenty of tropes (that site is incredibly comprehensive, and it’s still a fantasy series) but, by my count, 5 tropes are subverted, 6 are averted, 3 are deconstructed, 2 are played with, 1 is inverted, and 1 is parodied. ↩︎

-

Many other series would have limited the number of characters, killing off or sending away certian characters, for the efficiency of the novel. Erikson, instead, stuck to his guns, continuing the practices that make the series great, sometimes providing an emotional backdrop for 25 or more characters in a single chapter. ↩︎